The Crooked House: A Sad Demise to a Proud Emblem of Mining

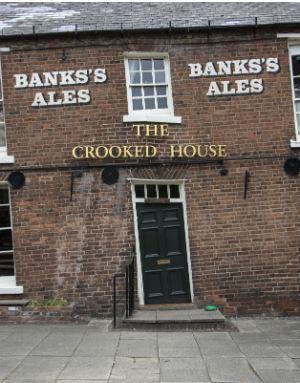

The Crooked House pub was an iconic Black Country landmark located in Himley, South Staffordshire. For many years, it was synonymous with subsidence – resurfacing every now and then as a quirky news article about its wonky shape, often with archive footage of drinkers seemingly rolling a glass uphill when the table was level due to the floor angle.

Now, it is the subject of national and international controversy after a devastating fire swept through the building on 5th August 2023 and the centre of police investigations after a hasty and allegedly unlawful demolition. Dots are being joined together in connection with the owners, their business interests and past history. The true story is yet to be fully ascertained as to what really happened to this national treasure of a building.

This piece won’t dwell on the controversy, more on the building’s rich legacy – a trip down memory lane into the story of the local mining operations and a delve into what may have been responsible for its appearance. Why the name The Crooked House?

A Long History of The Crooked House pub above and below Ground

Built originally in 1765 as the main farmhouse for Oak Farm, the building really stood the test of time, making its recent destruction even more painful for the local community. In the 19th Century, Staffordshire was a hugely industrial county, with a vast number of coal mining operations as well as those looking to exploit other favourable minerals like fireclay and ironstone, worked out of seams deep below the rolling countryside.

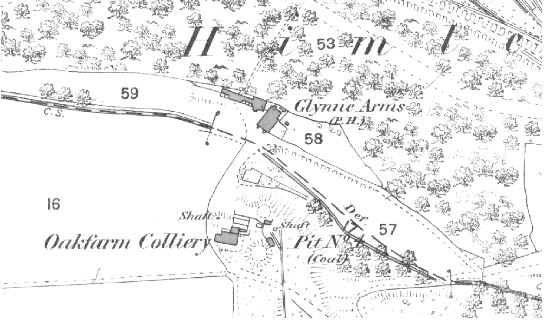

At the time, the Earl of Dudley owned Himley Colliery which covered a large area around the building.Historic sources also show the presence of Oakfarm Colliery to the south of the pub. Eventually, the mining operations beneath and around the structure is thought to have led to gradual sinking of the building giving it its characteristic appearance of being over 1 metre lower at one end than the other, with a tilt of around 15 degrees.

In the 1830s, the farmhouse was converted into a pub, serving local patrons some of Staffordshire’s finest ales, boarding weary travellers on a tour of the Black Country or simply passing through, serving up local delicacies like faggots and “proper gravy” (according to their most recent menu). .

An extract of 1882 Ordnance Survey mapping named the pub as The Glynne Arms, paying tribute to the family who owned the land it sat on. But, to the locals in the 1830s it was called Siden House, “siden” meaning crooked in the Black Country dialect. The local term stuck but it wasn’t until 2002 it was formally renamed Crooked House until its sad demise.

The building has had a precarious past: damaged by fire on more than one occasion, scheduled for demolition after being declared unsafe and been the target of numerous break-ins and burglaries.

Managing the Structure

The settlement issues have been addressed at various points in the building’s past, first with the addition of the celebrated buttressing in the early 1900s, it was also secured using metal tie rods in the 1950s following the threat of demolition, it is assumed,to mitigate potential public safety issues, in an effort to keep it open. . The tie rods could be seen in the majority of photographs of the pub in recent years, with the large metal plates spaced periodically across the front of the pub with a bolt in the centre.

What is hidden are the metal rods running through the building to the otherside where again, a large black anchor plate can be seen. These plates and the rod hold the sides of the property together, aiming to stop any outward movement. This is not uncommon for buildings of this age, especially when they are prone to or have experienced ground movement.

What caused the Subsidence?

But what caused this building to become “crooked” in the first place? We know from historic records that the area surrounding the pub and indeed beneath it have been subjected to intense mining operations, not just for coal but also for fireclay.This was often interbedded within the coal measures and mining companies would have been more than happy to exploit it if it was there for the taking.

These deposits were formed millions years ago through the layering of organic matter, compaction and intense heat and pressure and lie in broadly horizontal layers below the surface. When these deposits were mined they left voids in the ground where the rock once was. In many cases, this can be done in a stable way so that resultant movement is minimal. There are still underground mining operations active today in the UK that cause little to no impact to the surface above them, but not so with the site that the Crooked House sat on.

If voids exist beneath the surface, whether naturally occurring or man-made, stresses may occur over time which can, on occasion, cause the roof of the void or working to collapse, especially with older styles of workings no longer actively managed or maintained. The overlying rock will then fall into this collapsed area, often choking it temporarily, leading to a slow and gradual domino effect.

In this example, the mining void will slowly migrate over time to the surface, as the material above gradually falls to fill the gap below. This can cause depressions at the surface, sagging of the ground and in some extreme cases, holes. Some sources suggest that undermining is to blame, whether existing mine workings or in this instance, the foundations of a much loved watering hole. In the total absence of building regulations in the 1700s, we can be fairly sure that construction standards didn’t account for the less-than-perfect ground conditions and the rapid expansion of mining activity and traffic that would at one point exist beneath it.

Restoring a National Treasure using Today’s Standards?

Today is a different story. When dealing with properties in mining areas, especially when we know historic mining features to be present, we can account for these in the building and design stages. Whether you excavate and secure these features before proceeding to build, or sit the property on piled foundations to account for any possibility of movement in the future from the ground below,, you can mitigate the risk from historic mine workings and protect the structural integrity of a property sat above them.

Regardless of the eventual outcome of official investigations, we have lost a national treasure – one that may very well make a welcome return in the future. A building so quirky, so steeped in history and so loved, that the nation has rallied together to petition to have this historic landmark rebuilt brick by brick, buttresses and tie rods included. It would not be the same building if it wasn’t crooked and didn’t represent the long and proud mining history of the Black Country, as well as one of the country’s most loved pubs.

For more information on our market leading mining archive, ground investigations and mining risk assessment services, contact us at mining@groundsure.com or call us on 01273 257 755.

Date:

Aug 24, 2023

Author:

Tom Harvey-James