Newcastle Mining History: Toil, Tragedy and Evolution

The phrase “Coals to Newcastle” uniquely weds the image of past coal mining to the northeastern city. But there are also large tracts of subterranean cavities that were also used to extract fireclay close to the coal mine shafts along the edge of the Tyne valley through a rapidly urbanising part of the city.

The West End of Newcastle has been a place in constant flux for years. In the last century, the economic climate of the area has changed dramatically, from a booming industrial zone at the beginning of the 20th Century, to the decline and unemployment of the post war years stretching through to present day.

At the same time, the urban landscape has fluctuated and shifted from slum clearances to mass council housing projects, privatisation schemes to high-rise tower block developments, interspersed with large-scale demolition, dispersal and ‘regeneration’ schemes.

And while this constant evolution continued above ground, an extensive labyrinth of shafts and tunnels has remained largely forgotten or ignored, except perhaps for a simple memorial statue – but more about that in a minute.

Charting the Labyrinth

A plaque above a gated entrance reveals the entrance to a drift mine that was part of the Scotswood Delaval mine. It was part of an extensive network of mines on land owned by the wealthy Delaval family who ran the estate from their nearby palatial manor house. The family had somewhat of a reputation for their wild and eccentric lifestyle, but also for exploiting their estate workers.

A drift mine is an underground mine in which the entry or access is above water level and generally on the slope of a hill, driven horizontally into the seam. A drift may or may not intersect the ground surface and follows a mineral deposit, as distinguished from a crosscut that intersects it, or a level or gallery, which may do either.

The drift was part of the Delaval Benwell Colliery which was closed in 1901. It marks one of the openings that leads to a maze of interconnecting workings including the Montagu pit. Parts of it may be related to a unique construction dating as far back as 1670 to drain water from pits at West Kenton, Newbiggin and Whorlton down to the Tyne and in its later life operated as a railway incline that linked to the former Scotswood, Newburn and Wylam Railway.

To the west, at Bell’s Close near the Scotswood Bridge, there was the exit of another tunnel, called Kitty’s Drift. This carried an underground railway 3 miles from East Kenton Colliery down to the River Tyne, built around 1770. Its use for transporting coal was taken over by the Kenton and Coxlodge waggonway in 1808. Its exact course is now not known but historically notable as possibly the earliest underground railway in the world.

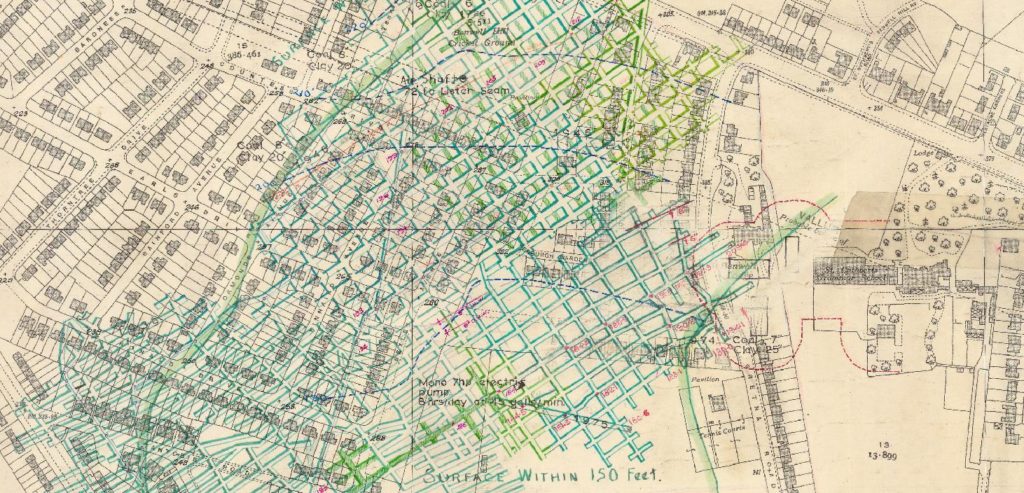

Images of the location of former coal and fireclay mines at Scotswood, from our mining records archive.

The mines formed an extensive maze of pillar and stall workings to extract both coal and fireclay, but often in different locations. You can see the above extract from our mining records that show the widespread development of housing, as well as running underneath the historic path of Hadrian’s Wall.

The fireclay was used to make construction bricks to feed the expansion of Newcastle and other cities. After the first world war. Adamsez Ltd, sanitary ware manufacturers, who had a large factory in Scotswood diversified into the manufacture of firebricks under the name, Scotswood Furnace Company and latterly Adams Pict Ltd. They were also used in furnaces as excellent fire retardant and insulation materials.

Toil, Tragedy and Remembrance

While some workings were exhausted and shut in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, work continued into the 1920s, when tragedy struck. Generations of men and boys had toiled underground in back breaking conditions, aware of the physical risks in front of them.

On March 30, 1925, a pair of miners – only on duty because two colleagues had slept in – fired three shots to straighten the pit face. Straight away there was trouble: foul-smelling water seeped through the face and then a dull thud was heard followed by consternation as miners ran for their lives. Methane extinguished the miners’ lamps, plunging 148 men and boys into crushing darkness, and millions of gallons of water roared through the pit.

With fearful families waiting outside the pit, dazed miners gradually emerged into the light of day, and it slowly dawned that 38 of their colleagues had not made it. 22 of the victims came from Scotswood, devastating the small, close-knit community. Bodies were left in the mine for months as pumps were unable to clear the water.

A relief fund “answered by all classes of the community” raised £4,000 (around £250,000 in today’s money) for stricken families. Novelist AJ Cronin loosely based his 1935 novel, The Stars Look Down, on the Montagu disaster, followed by a 1940 film of the same name.

The commemorative statue in Scotswood following the 1925 tragedy. Image courtesy of Geograph.co.uk

Today, a statue in Scotswood commemorates the pitmen and boys who lost their lives on that dark day. After more than 200 years in operation, Montagu Pit closed its gates for the last time in November 1959.

As more coal seams were exhausted, more attention turned to fireclay to keep feeding demand for the firebricks. The Lister seam of the Scotswood mine was still in recorded production right up to 1975.

The mine entrance at Scotswood was restored and the plaque put up by Tyne & Wear County Council in 1986. Little else was considered about the site as it lay idle for many years but there have been more recent instances of the major roads to the south and west of Scotswood having been flooded by mine water, as existing outfalls have been overwhelmed. In recent years, the City Council has invested in improvements to the mine entrance to ensure that mine water transfers to a culvert that takes it to the River Tyne and not the roads and properties nearby.

Evolution and Adaption with Climate Change

But their influence could start to make itself known as our climate continues to change. It could cause two potential effects. Subsidence could accelerate 8-fold from its current levels in the next 30-50 years. This could undermine shallower workings and adits that criss-cross underneath a large part of the West of Newcastle around Scotswood and Benwell.

Medium projections also suggest a 20-25% increase in rainfall nationally, with disproportionately more in the north of England. Elevated surface (pluvial) flooding in a local level could overwhelm culverts already dealing with mine water emissions, as well as raise the subsurface groundwater levels for some time after the rainfall events have occurred. This can all create challenges for existing properties and new developments around past mining areas, whether coal or other minerals.

Bringing our history of the area up to date, the 2020s are seeing a continued evolution of the Scotswood area, with the regeneration of a 60-hectare site including a new estate of 1800 homes at the Rise which are due to be completed by 2026. It will be interesting to see how this development and all the surrounding neighbourhoods co-exist with the mining heritage and our evolving climate that lies around and beneath it.

Think ALL Mining types, Think Climate Change

Our Avista environmental report provide the most comprehensive view of past mining activity from both coal with a fully inclusive CON29M, together with reporting on more than 60 other minerals, including Fireclay, which are not typically covered in a traditional coal mining search.

Not only that, but in addition to contaminated land, planning and infrastructure searches (essential for rapidly changing urban areas), Avista also looks into the future thanks to our unique ClimateIndex™ analysis module. This looks at the potential forward impact of climate change on a property-specific basis for a 1-, 5- and 30-year period. This helps your client understand the risks from flooding, subsidence and coastal erosion now, for a typical mortgage term and for within most resale periods.

It also enables your practice to be compliance-ready with future changes to guidance on advising clients about climate change from lenders and legal associations.

For more information about Avista, past mining risks and the ClimateIndex™ module, contact us on 01273 257 755 or email us at info@groundsure.com

References

P L Younger ‘Making Water’ p.121-157 in J D Mather Ed. ‘200 years of British Hydrogeology’, Geological Society Special Publication 225 (2004)

https://sitelines.newcastle.gov.uk/SMR/5114

https://www.scottishbrickhistory.co.uk/adams-pict-firebrick-co-ltd-scotswood-on-tyne-newcastle/

http://www.dmm.org.uk/colliery/s023.htm

http://www.dmm.org.uk/colliery/m009.htm

https://co-curate.ncl.ac.uk/resources/view/68497/

https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/history/newcastle-pit-disaster-montagu-scotswood-20275565

https://businessmondays.co.uk/new-phase-for-scotswood-regeneration-scheme/

Date:

Aug 2, 2022

Author:

David Kempster