Fictitious entries – what’s the truth?

If you are in the business of conveying factual information – the production of dictionaries, encyclopedias, and maps – protecting your work from theft, or copyrighting your work, is difficult.

The purpose of copyrighting is twofold; it is designed to a) ensure people are recognised for the work they produce and b) ensure that a person may benefit solely from work they have produced and not have it exploited by others.(1)

When copyrighting an individual’s work the work itself needs to have a minimal form of originality to connect it to its creator. When conveying black and white facts, making them original and unique to you is not an easy task.

Out of this conundrum the concept of fictitious entries was borne and there are many examples of this in certain factual publications over time:

- Lillian Virginia Mountweazel

The 1975 edition of the New Columbia Encyclopedia held an entry regarding Ms Mountweazel – a much celebrated photographer of American letterboxes, her collection of works was called ‘Flags up’ and she tragically died in an explosion at age 31 while on assignment for Combustibles magazine.(2) Sounds like a fascinating woman. A completely fictitious woman, but fascinating nonetheless. This case of a fictitious entry is so famous that the word mountweazel is now defined by dictionary.com as ‘any invented word or name inserted in a reference work by a publisher for the purpose of detecting plagiarism’.

- Zzxjoanw

The word above was published in Robert Huges ‘Music Lovers’ Encyclopedia of 1903 and was defined as ‘a Maori word for drum’. As there are no z, x or j’s in the Maori language this is certainly not the case. However, it did persist in publications right up to the 1950s.(3)

- Agloe, NY

Is a ‘paper town’ created by the Esso company in the early 1930s. The interesting thing about this fake town is that it eventually became a reality for a time. An enterprising person saw the town on a map and decided to set up a general store for it in the 1950s. Over the next 40 years the fictional town of Agloe grew with a gas station and two houses established. Today Agloe is no longer in existence, the buildings there have been abandoned and it is no longer recognised on maps.(4)

When it comes to Cartography (mapping), historically, many cartographers created deliberate errors in maps to prove their origin. This ranged from kinks in rivers and the addition of small buildings to exaggerated curves in roads and the creation of small roadways. In the world of mapping these fictitious entries are known collectively as ‘trap streets’.(5)

The UK is no stranger to this phenomenon either. The town of Argleton in Lancashire has appeared on Google maps for years, however it is located in the middle of fields in the countryside – not a building in sight.

Google Maps (accessed June 2016)

Its not clear if this anomaly is simply a mistake or a deliberate insertion by the cartographer for copyright reasons.(6) After many blogs and news stories highlighted Argleton as a fictitious town it has been removed from Google maps.

Other examples of trap streets that are still visible on mapping web sites include:

Kemp Avenue, Toronto

Open Street Map shows a street off Ways Lane in Toronto; Kemp Avenue. When consulting Google maps it can be seen that this Avenue does not appear to exist and in fact comprises residential gardens.

OpenStreetMap (accessed October 2016)

Google maps (accessed October 2016)

Kerbela Street, Shrewsbury

Teleatlas shows an offshoot of Meadow Farm Lane noted as Kerbela Street. Upon consulting Google maps it can be seen that this street does not appear to exist and in fact a building is situated in its place.

Teleatlas (accessed October 2016)

Google maps (accessed October 2016)

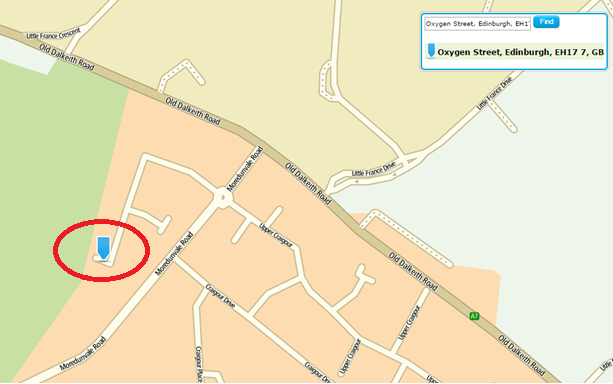

Oxygen Street, Edinburgh

Much like the example above, Teleatlas shows an offshoot of Nether Craigour noted as Oxygen Street. Upon consulting Google maps it can be seen that this street does not appear to exist and in fact a building is situated in its place.

Teleatlas (accessed October 2016)

Google maps (accessed October 2016)

Over the years, and as you can see from the preceding examples, cartographers have made ‘trap streets’ as small and unobtrusive as possible so as not to put the user off track. By the 1980s the use of trap streets was rumoured to have ceased and their appearance on mapping has slowly been petering out since this time, however some still stubbornly remain. Cartographers have now found more sophisticated ways to enable mapping to be copyrighted and also maintain the integrity of the information contained within the maps. For example in 2001, the Automobile Association was ordered to pay £20 million for infringing on another outfit’s mapping copyrights.(7) How was the infringement proven? Through the use of small style markers, or fingerprints in the mapping, for example specific road widths known only to the original cartographer.(8) So whilst trap streets are now becoming a thing of the past, modern technology has allowed cartographers to continue to protect their work!

References

- Katleen Janssen & Jos Dumortier, The Protection of Maps and Spatial Databases in Europe and the United States by Copyright and the Sui Generis Right, 24 J. Marshall J. Computer & Info. L. 195 (2006)

- The New Yorker (2005). ‘Not a Word’ http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2005/08/29/not-a-word

- ‘Fun With Copyright Traps: 10 Hoax Definitions, Paper Towns, and Other Things That Don’t Exist’ http://mentalfloss.com/article/30957/fun-copyright-traps-10-hoax-definitions-paper-towns-and-other-things-don%E2%80%99t-exist

- Atlas Obscura. ‘Agloe, New York’ http://www.atlasobscura.com/places/agloe-new-york

- Cabinet Magazine (2012). ‘Trap Streets’ http://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/47/bridle.php

- The Guardian (2009). ‘Welcome to Argleton, the town that doesn’t exist’ https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2009/nov/03/google

- The Guardian (2001) ‘Copying maps costs AA £20m’ https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2001/mar/06/andrewclark

- The Week (2013) Trap streets: ‘The crafty trick mapmakers use to fight plagiarism’ http://theweek.com/articles/466184/trap-streets-crafty-trick-mapmakers-use-fight-plagiarism

Date:

Dec 2, 2016

Author:

Kate Goodall